|

|

|

CAPÍTULO 1 INTRODUÇÃO |

|

"Unless the lower rivers are allowed to reassert their natural function as exporters of salt to the ocean, today's productive lands will eventually become salt encrusted and barren."

"A menos que os rios mais baixos possam reafirmar sua função natural como exportadores de sal para o oceano,

as terras produtivas de hoje acabarão se tornando incrustadas e estéreis ao sal."

|

|

This electronic book deals with principles of hydrologic science and their application to the solution of hydraulic, hydrologic, and water resources engineering problems, including the water-related environmental issues. Este livro eletrônico lida com os princípios da ciência hidrológica e sua aplicação na solução de problemas de engenharia de recursos hidráulicos, hidrológicos e hídricos, incluindo os problemas ambientais relacionados à água. This introductory chapter is divided into six sections. Section 1.1 defines hydrology and engineering hydrology. Section 1.2 describes the hydrologic cycle, a fundamental tenet of hydrologic science. Section 1.3 describes the closely related concepts of catchment and hydrologic budget. Section 1.4 explains the use of hydrologic knowledge in the solution of typical problems of hydraulic and hydrologic engineering. Section 1.5 elaborates on the various approaches used to solve problems of engineering hydrology. Section 1.6 discusses surface runoff, flood hydrology, and catchment scale. The concept of catchment scale is used in this book to develop a framework for the study of hydrologic models, methods, and techniques. Este capítulo introdutório está dividido em seis seções. A Seção 1.1 define hidrologia e hidrologia de engenharia. A Seção 1.2 descreve o ciclo hidrológico, um princípio fundamental da ciência hidrológica. A Seção 1.3 descreve os conceitos intimamente relacionados de captação e orçamento hidrológico. A Seção 1.4 explica o uso do conhecimento hidrológico na solução de problemas típicos da engenharia hidráulica e hidrológica. A Seção 1.5 detalha as várias abordagens usadas para resolver problemas de hidrologia de engenharia. A Seção 1.6 discute o escoamento superficial, a hidrologia das inundações e a escala de captação. O conceito de escala de captação é usado neste livro para desenvolver uma estrutura para o estudo de modelos, métodos e técnicas hidrológicos. |

1.1 DEFINIÇÃO DE HIDROLOGIA EM ENGENHARIA

|

|

Hydrology is one of the earth sciences. It studies the waters of the earth, their occurrence, circulation and distribution, their chemical and physical properties, and their relation to living things. Hydrology encompasses surface water hydrology and groundwater hydrology; the latter, however, is considered to be a subject in itself. Other related earth sciences include climatology, meteorology, geology, geomorphology, sedimentology, geography, and oceanography.

A hidrologia é uma das ciências da terra. Estuda as águas da terra, sua ocorrência, circulação e distribuição, suas propriedades químicas e físicas e sua relação com os seres vivos. A hidrologia abrange a hidrologia das águas superficiais e das águas subterrâneas; o último, no entanto, é considerado um sujeito em si. Outras ciências da terra relacionadas incluem climatologia, meteorologia, geologia, geomorfologia, sedimentologia, geografia e oceanografia.

Engineering hydrology is an applied earth science. It uses hydrologic principles in the solution of engineering problems arising from human exploitation of the water resources of the Earth. In its broadest sense, engineering hydrology seeks to establish relations defining the spatial, temporal, seasonal, annual, regional, or geographical variability of water, with the aim of ascertaining societal risks involved in sizing hydraulic structures and systems.

A hidrologia da engenharia é uma ciência da terra aplicada. Utiliza princípios hidrológicos na solução de problemas de engenharia decorrentes da exploração humana dos recursos hídricos da Terra. Em seu sentido mais amplo, a hidrologia da engenharia busca estabelecer relações que definam a variabilidade espacial, temporal, sazonal, anual, regional ou geográfica da água, com o objetivo de determinar os riscos sociais envolvidos no dimensionamento de estruturas e sistemas hidráulicos.

1.2 CICLO HIDROLÓGICO

|

|

The hydrologic cycle describes the continuous recirculatory transport of the waters of the earth, linking atmosphere, land, and oceans. The process is quite complex, containing many subcycles. To explain it briefly, water evaporates from the ocean surface, driven by energy from the sun, and joins the atmosphere, moving inland. Once inland, atmospheric conditions act to condense and precipitate water onto the land surface, where, driven by gravitational forces, it returns to the ocean through streams and rivers.

O ciclo hidrológico descreve o transporte recirculatório contínuo das águas da terra, ligando atmosfera, terra e oceanos. O processo é bastante complexo, contendo muitas sub-motocicletas. Para explicar brevemente, a água evapora da superfície do oceano, impulsionada pela energia do sol, e se junta à atmosfera, movendo-se para o interior. Uma vez no interior, as condições atmosféricas agem para condensar e precipitar a água na superfície terrestre, onde, impulsionadas por forças gravitacionais, retornam ao oceano através de córregos e rios.

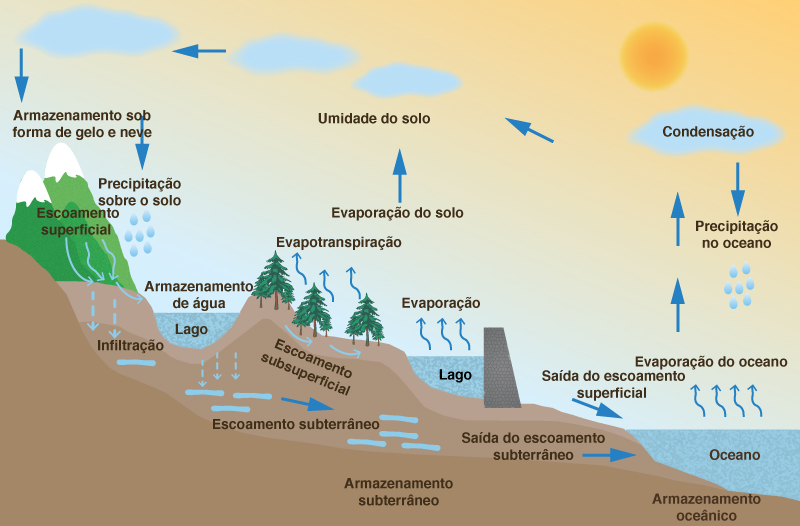

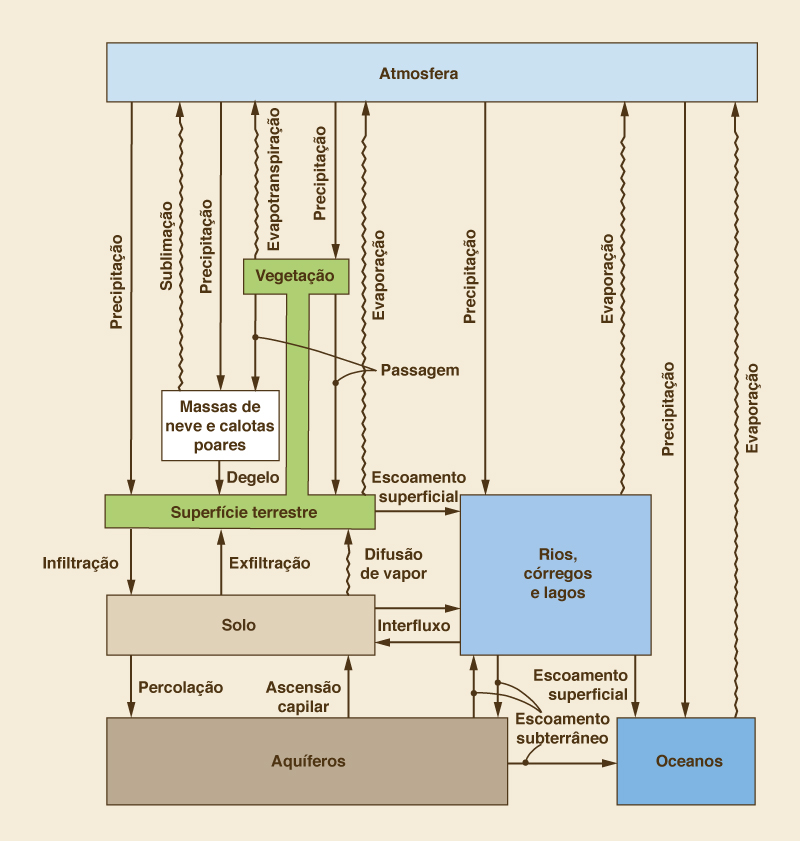

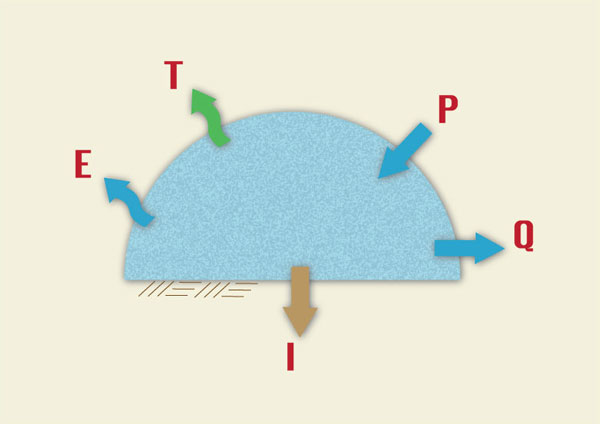

Figure 1-1 shows a pictorial representation of the hydrologic cycle. A schematic view, including the interaction between the various phases and water-holding elements, is shown in Fig. 1-2 [2]. This schematic includes all physical processes relevant to engineering hydrology. Precipitation and other liquid-transport phases are represented by straight arrows, while evaporation and other vapor-transport phases are represented by wavy arrows.

A Figura 1-1 mostra uma representação pictórica do ciclo hidrológico. Uma vista esquemática, incluindo a interação entre as várias fases e os elementos de retenção de água, é mostrada na Fig. 1-2 [2]. Este esquema inclui todos os processos físicos relevantes para a hidrologia de engenharia. A precipitação e outras fases de transporte de líquido são representadas por setas retas, enquanto a evaporação e outras fases de transporte de vapor são representadas por setas onduladas.

Fig. 1-1 The hydrologic cycle. |

Fig. 1.2 Schematic view of the hydrologic cycle (By permission from "Dynamic Hydrology," |

The water-holding elements of the hydrologic cycle are:

Os elementos de retenção de água do ciclo hidrológico são:

- Atmosphere

- Atmosfera

- Vegetation

- Vegetação

- Snowpack and icecaps

- Neve e calotas polares

- Land surface

- Superfície da terra

- Soil

- Solo

- Streams, lakes, and rivers

- Córregos, lagos e rios

- Aquifers

- Aquíferos

- Oceans.

- Oceanos.

The liquid-transport phases of the hydrologic cycle are:

As fases de transporte de líquido do ciclo hidrológico são:

- Precipitation from the atmosphere onto land surface

- Precipitação da atmosfera na superfície terrestre

- Throughfall from vegetation onto land surface

- Queda da vegetação na superfície da terra

- Melt from snow and ice onto land surface

- Derreta da neve e gelo na superfície da terra

- Surface runoff from land surface to streams, lakes, and rivers, and from streams, lakes , and rivers to oceans

- Escoamento superficial da superfície da terra para córregos, lagos e rios e de córregos, lagos e rios para oceanos

- Infiltration from land surface to soil

- Infiltração da superfície da terra no solo

- Exfiltration from soil to land surface

- Exfiltração do solo para a superfície terrestre

- Interflow from soil to streams, lakes, and rivers and vice versa

- Interfluxo do solo para córregos, lagos e rios e vice-versa

- Percolation from soil to aquifers

- Percolação do solo para aqüíferos

- Capillary rise from aquifers to soil

- Elevação capilar dos aquíferos para o solo

- Groundwater flow from streams, lakes, and rivers to aquifers and vice versa, and from aquifers to oceans and vice versa.

- As águas subterrâneas fluem de córregos, lagos e rios para aquíferos e vice-versa, e de aquíferos para oceanos e vice-versa.

The vapor-transport phases of the hydrologic cycle are:

As fases de transporte de vapor do ciclo hidrológico são:

- Evaporation from land surface, streams, lakes, rivers, and oceans to the atmosphere

- Evaporação da superfície terrestre, córregos, lagos, rios e oceanos para a atmosfera

- Evapotranspiration from vegetation to the atmosphere

- Evapotranspiração da vegetação para a atmosfera

- Sublimation from snowpack and icecaps to the atmosphere

- Sublimação da neve e calotas de gelo para a atmosfera

- Vapor diffusion from soil to land surface.

- Difusão de vapor do solo para a superfície da terra.

1.3 BACIA HIDROGRÁFICAS E SEU BALANÇO

|

|

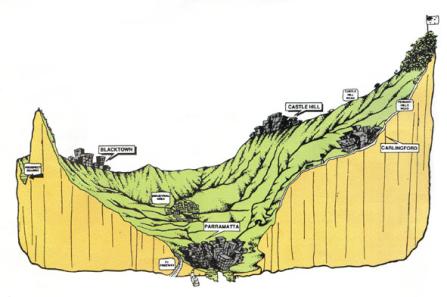

A catchment is a portion of the earth's surface that collects runoff and concentrates it at its furthest downstream point, referred to as the catchment outlet (Fig. 1-3). The runoff concentrated by a catchment flows either into a larger catchment or into the ocean. The place where a stream enters a larger stream or body of water is referred to as the mouth.

Uma bacia hidrográfica é uma porção da superfície da Terra que coleta o escoamento superficial e o concentra no ponto mais a jusante, conhecido como saída da bacia hidrográfica (Fig. 1-3). O escoamento concentrado por uma bacia flui para uma bacia maior ou para o oceano. O local em que um riacho entra em um riacho ou corpo de água maior é chamado de boca.

Fig. 1-3 The Upper Parramatta River catchment, New South Wales, Australia. |

In U.S. hydrologic practice, the terms watershed and basin are commonly used to refer to catchments. Generally, watershed is used to describe a small catchment (stream watershed), whereas basin is reserved for large catchments (river basins). In this book, the word catchment is used without a specific connotation of scale, whereas the use of the words watershed and basin follow established practice.

Na prática hidrológica dos EUA, os termos bacia e bacia são comumente usados para se referir a bacias hidrográficas. Geralmente, a bacia hidrográfica é usada para descrever uma pequena bacia hidrográfica (bacia hidrográfica), enquanto a bacia é reservada para bacias hidrográficas grandes (bacias hidrográficas). Neste livro, a palavra captação é usada sem uma conotação específica de escala, enquanto o uso das palavras bacia e bacia segue a prática estabelecida.

The interpretation of the hydrologic cycle within the confines of a catchment leads to the concept of hydrologic budget. The hydrologic budget refers to an accounting of the various transport phases of the hydrologic cycle within a catchment, with the aim of ascertaining their relative magnitudes. The following is a hydrologic budget equation that considers both surface water and groundwater:

A interpretação do ciclo hidrológico dentro dos limites de uma bacia hidrográfica leva ao conceito de orçamento hidrológico. O orçamento hidrológico refere-se a uma contabilidade das várias fases de transporte do ciclo hidrológico dentro de uma bacia hidrográfica, com o objetivo de determinar suas magnitudes relativas. A seguir, é apresentada uma equação do orçamento hidrológico que considera as águas superficiais e subterrâneas:

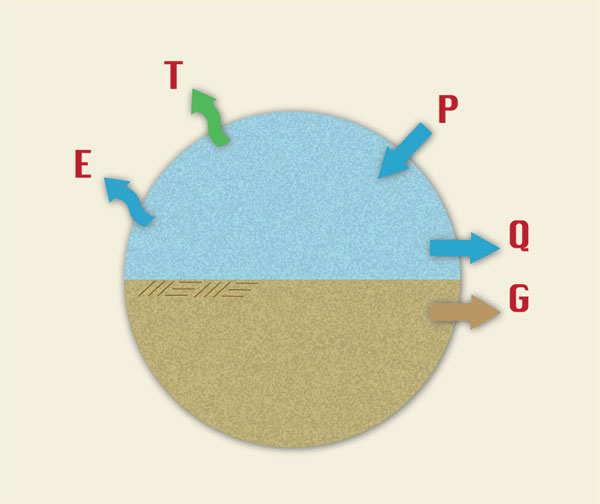

| ΔS = P - ( E + T + G + Q ) | (1-1) |

in which ΔS = change in storage, P = precipitation, E = evaporation, T = evapotranspiration, G = groundwater outflow, and Q = surface runoff. Within a given time span, the change in water volume remaining in storage in a catchment is the difference between precipitation and the sum of evaporation, evapotranspiration, groundwater outflow, and surface runoff.

in which ~S = change in storage, P = precipitation, E = evaporation, T = evapotranspiration, G = groundwater outflow, and Q = surface runoff. Within a given time span, the change in water volume remaining in storage in a catchment is the difference between precipitation and the sum of evaporation, evapotranspiration, groundwater outflow, and surface runoff.

In hydrologic practice, the terms of Eq. 1-1 are expressed in units of water depth, i.e., a water volume uniformly distributed over the catchment area. Under equilibrium conditions, ΔS = 0, and Eq. 1-1 reduces to (Fig. 1-4):

Na prática hidrológica, os termos da Eq. 1-1 são expressos em unidades de profundidade da água, isto é, um volume de água uniformemente distribuído sobre a área de captação. Sob condições de equilíbrio, ~S = 0 e Eq. 1-1 reduz para (Fig. 1-4):

| P = E + T + G + Q | (1-2) |

Fig. 1-4 A hydrologic budget that considers both surface water |

A hydrologic budget equation that considers only surface water is:

Uma equação do orçamento hidrológico que considera apenas a água superficial é:

| ΔS = P - ( E + T + I + Q ) | (1-3) |

in which I = infiltration, and all other terms have been already defined. Within a given time span, under equilibrium conditions, Eq. 1-3 reduces to (Fig. 1-5):

em que I = infiltração e todos os outros termos já foram definidos. Dentro de um determinado período de tempo, sob condições de equilíbrio, a Eq. 1-3 reduz para (Fig. 1-5):

| P = E + T + I + Q | (1-4) |

Fig. 1-5 A hydrologic budget that considers only surface water. |

Note that there may be some double counting in Eq. 1-4, because infiltration can convert into evaporation through lakes and wetlands, into evapotranspiration through vegetation, and into surface runoff (baseflow) through exfiltration.

Note that there may be some double counting in Eq. 1-4, because infiltration can convert into evaporation through lakes and wetlands, into evapotranspiration through vegetation, and into surface runoff (baseflow) through exfiltration.

Equation 1-4 is often expressed in reduced form:

A equação 1-4 é frequentemente expressa em forma reduzida:

| Q = P - L | (1-5) |

in which L = losses, or hydrologic abstractions, equal to the sum of evaporation E, evapotranspiration T, and infiltration I. Equation 1-5 states that runoff is equal to precipitation minus the aggregate of all losses. This concept is the basis of many practical methods of runoff computation (Chapters 4 and 5).

in which L = losses, or hydrologic abstractions, equal to the sum of evaporation E, evapotranspiration T, and infiltration I. Equation 1-5 states that runoff is equal to precipitation minus the aggregate of all losses. This concept is the basis of many practical methods of runoff computation (Chapters 4 and 5).

1.4 USOS DA HIDROLOGIA EM ENGENHARIA

|

|

Engineering hydrology seeks to answer questions of the following type:

A hidrologia de engenharia procura responder a perguntas do seguinte tipo:

What is the maximum probable flood at a proposed or existing dam site (Fig. 1-6)?

Qual é a máxima inundação provável provável em um local de barragem proposto ou existente (Fig. 1-6)?

How does a catchment's water yield vary from season to season, and from year to year?

Como a produção de água de uma bacia hidrográfica varia de estação para estação e de ano para ano?

What is the relationship between a catchment's surface water and groundwater resources?

Qual é a relação entre a água superficial de uma bacia hidrográfica e os recursos subterrâneos?

When evaluating low flow characteristics, what flow level can be expected to be exceeded 90 percent of the time?

Ao avaliar características de baixo fluxo, qual nível de fluxo pode ser excedido em 90% das vezes?

Given the natural variability of streamflows, what is the appropriate size of an instream storage reservoir?

Dada a variabilidade natural dos fluxos, qual é o tamanho apropriado de um reservatório de armazenamento em fluxo?

What hydrologic hardware (e.g., rainfall sensors) and software (computer models) are needed for real-time flood forecasting?

Que hardware hidrológico (por exemplo, sensores de chuva) e software (modelos de computador) são necessários para a previsão de inundações em tempo real?

In seeking answers to these questions, engineering hydrology uses analysis and measurement. Hydrologic analysis aims to develop a methodology to quantify a certain phase or phases of the hydrologic cycle, for instance, precipitation, infiltration, or surface runoff. The unit hydrograph technique (Chapter 5) is a good example of a time-tested method of hydrologic analysis. Field measurements such as stream gaging (Chapter 3) complement and verify the analysis. Statistical methods, e.g., linear regression (Chapter 7), supplement hydrologic analysis and/ or measurement.

Na busca de respostas para essas perguntas, a hidrologia da engenharia usa análise e medição. A análise hidrológica visa desenvolver uma metodologia para quantificar uma determinada fase ou fases do ciclo hidrológico, por exemplo, precipitação, infiltração ou escoamento superficial. A técnica de hidrografia unitária (capítulo 5) é um bom exemplo de método de análise hidrológica testado pelo tempo. Medidas de campo, como medição de fluxo (capítulo 3), complementam e verificam a análise. Os métodos estatísticos, por exemplo, regressão linear (Capítulo 7), complementam a análise hidrológica e / ou medição.

Generally, the hydrologic engineer is interested in describing either flow rates or volumes, including their spatial, temporal, seasonal, annual, regional, or geographical variability. Flow rates (discharges) are commonly expressed in cubic meters per second or cubic feet per second; volumes are expressed in cubic meters, cubic hectometers (1 hectometer is equal to 1 million cubic meters), or acre-feet. In engineering hydrology, volumes are often expressed in depth units (millimeters, centimeters, or inches), intended to represent a uniform water depth over the catchment area.

Geralmente, o engenheiro hidrológico está interessado em descrever taxas de fluxo ou volumes, incluindo sua variabilidade espacial, temporal, sazonal, anual, regional ou geográfica. As vazões (descargas) são comumente expressas em metros cúbicos por segundo ou pés cúbicos por segundo; os volumes são expressos em metros cúbicos, hectômetros cúbicos (1 hectômetro é igual a 1 milhão de metros cúbicos) ou acres-pés. Na hidrologia da engenharia, os volumes são frequentemente expressos em unidades de profundidade (milímetros, centímetros ou polegadas), destinadas a representar uma profundidade uniforme da água sobre a área de captação.

Fig. 1-6 Emergency spillway at Oroville Dam, Northern California. |

1.5 ABORDAGENS DA HIDROLOGIA EM ENGENHARIA

|

|

There are many approaches to engineering hydrology. These can be thought of as models seeking to represent the behavior of the prototype (i.e., the real world). Generally, models can be classified as either: (a) material, or (b) formal. A material model is a physical representation of a prototype, simpler in structure and with properties similar to those of the prototype. A formal model is a mathematical abstraction of an idealized situation that preserves the important structural properties of the prototype [4].

Existem muitas abordagens para a engenharia hidrológica. Estes podem ser considerados modelos procurando representar o comportamento do protótipo (isto é, o mundo real). Geralmente, os modelos podem ser classificados como: (a) material ou (b) formal. Um modelo de material é uma representação física de um protótipo, de estrutura mais simples e com propriedades semelhantes às do protótipo. Um modelo formal é uma abstração matemática de uma situação idealizada que preserva as importantes propriedades estruturais do protótipo [4].

Material models can be either iconic or analog. Iconic models are simplified representations of real-world hydrologic systems, such as lysimeters, rainfall simulators, and experimental watersheds (Fig. 1-7). Analog models are those that base their measurements on substances different from those of the prototype, such as the flow of electrical current to represent the flow of water.

Os modelos de materiais podem ser icônicos ou analógicos. Modelos icônicos são representações simplificadas de sistemas hidrológicos do mundo real, como lisímetros, simuladores de chuva e bacias hidrográficas experimentais (Fig. 1-7). Modelos analógicos são aqueles que baseiam suas medições em substâncias diferentes daquelas do protótipo, como o fluxo de corrente elétrica para representar o fluxo de água.

Fig. 1-7 The USDA ARS Coshocton weighing lysimeter. |

In engineering hydrology, all formal models are mathematical in nature; hence the use of the term mathematical model to refer to all formal models. Unless specifically stated otherwise, the term "model" will be used in this book to refer to a mathematical model. The latter is by far the most widely used model type in engineering hydrology.

Na hidrologia de engenharia, todos os modelos formais são de natureza matemática; daí o uso do termo modelo matemático para se referir a todos os modelos formais. Salvo indicação em contrário, o termo "modelo" será usado neste livro para se referir a um modelo matemático. Este último é de longe o tipo de modelo mais utilizado em hidrologia de engenharia.

Mathematical models can be either: (1) theoretical, (2) conceptual, or (3) empirical. A theoretical model is founded on a set of general laws; conversely, an empirical model is largely based on inferences derived from the analysis of data. A conceptual model lies somewhere in between theoretical and empirical models.

Os modelos matemáticos podem ser: (1) teórico, (2) conceitual ou (3) empírico. Um modelo teórico é baseado em um conjunto de leis gerais; por outro lado, um modelo empírico é amplamente baseado em inferências derivadas da análise de dados. Um modelo conceitual está entre os modelos teórico e empírico.

In engineering hydrology, four types of mathematical models are in current use: (1) deterministic, (2) probabilistic, (3) conceptual, and (4) parametric. A deterministic model is formulated by using laws of physical, chemical, and/or biological processes, as described by differential equations. A probabilistic model, whether statistical or stochastic, is governed by laws of chance or probability. Statistical models deal with observed samples, whereas stochastic models focus on the random properties of certain hydrologic time series; for instance, daily streamflows [5]. A conceptual model is a simplified representation of the physical processes, obtained by lumping spatial and/ or temporal variations, and described in terms of either ordinary differential equations or algebraic equations. A parametric model represents hydrologic processes by means of algebraic equations that contain key parameters to be determined by empirical means.

Na hidrologia de engenharia, atualmente existem quatro tipos de modelos matemáticos: (1) determinístico, (2) probabilístico, (3) conceitual e (4) paramétrico. Um modelo determinístico é formulado usando leis de processos físicos, químicos e / ou biológicos, conforme descrito por equações diferenciais. Um modelo probabilístico, estatístico ou estocástico, é governado por leis do acaso ou da probabilidade. Modelos estatísticos lidam com amostras observadas, enquanto modelos estocásticos se concentram nas propriedades aleatórias de certas séries temporais hidrológicas; por exemplo, fluxos diários [5]. Um modelo conceitual é uma representação simplificada dos processos físicos, obtida por agrupamentos de variações espaciais e / ou temporais, e descrita em termos de equações diferenciais ordinárias ou equações algébricas. Um modelo paramétrico representa processos hidrológicos por meio de equações algébricas que contêm parâmetros-chave a serem determinados por meios empíricos.

Methods of analysis in engineering hydrology can generally be classified under one of the four model types just mentioned. For instance, the kinematic wave routing technique (Chapters 4 and 9) is deterministic, being governed by a partial differential equation describing the mass and momentum balance of fluid mechanics. The Gumbel method of flood frequency analysis (Chapter 6) is probabilistic, being based on an extreme value probability law. The cascade of linear reservoirs (Chapter 10) is conceptual, seeking to simulate the complexities of catchment response by means of a series of hypothetical linear reservoirs. The rational method (Chapter 4) is parametric, with peak flow (for a given frequency) estimated on the basis of an empirically determined runoff coefficient.

Os métodos de análise em hidrologia de engenharia geralmente podem ser classificados em um dos quatro tipos de modelo mencionados acima. Por exemplo, a técnica de roteamento de ondas cinemáticas (capítulos 4 e 9) é determinística, sendo governada por uma equação diferencial parcial que descreve o balanço de massa e momento da mecânica de fluidos. O método Gumbel de análise de frequência de inundação (Capítulo 6) é probabilístico, baseando-se em uma lei de probabilidade de valor extremo. A cascata de reservatórios lineares (capítulo 10) é conceitual, buscando simular as complexidades da resposta da bacia hidrográfica por meio de uma série de reservatórios lineares hipotéticos. O método racional (capítulo 4) é paramétrico, com pico de fluxo (para uma determinada frequência) estimado com base em um coeficiente de escoamento determinado empiricamente.

In principle, deterministic models mimic physical processes and should, therefore, be closest to reality. In practice, however, the inherent complexity of physical phenomena generally limits the deterministic approach to well defined cases for which a clear cause-effect relationship can be demonstrated. Probabilistic methods are used to fit measured data (i.e., statistical hydrology) and to model random components (stochastic hydrology) in cases where their presence is readily apparent. Where simplicity is desired, conceptual and parametric methods and models continue to play an important role in engineering hydrology.

Em princípio, os modelos determinísticos imitam os processos físicos e, portanto, devem estar mais próximos da realidade. Na prática, no entanto, a complexidade inerente aos fenômenos físicos geralmente limita a abordagem determinística a casos bem definidos para os quais uma relação clara de causa-efeito pode ser demonstrada. Os métodos probabilísticos são usados para ajustar os dados medidos (isto é, hidrologia estatística) e modelar componentes aleatórios (hidrologia estocástica) nos casos em que sua presença é prontamente aparente. Onde a simplicidade é desejada, métodos e modelos conceituais e paramétricos continuam a desempenhar um papel importante na hidrologia da engenharia.

Hydrologic models can be either lumped or distributed. Lumped models can describe temporal variations but cannot describe spatial variations. A typical example of a lumped hydrologic model is the unit hydrograph (Chapter 5), which describes a catchment's unit response without regard to the response of individual subcatchments.

Hydrologic models can be either lumped or distributed. Lumped models can describe temporal variations but cannot describe spatial variations. A typical example of a lumped hydrologic model is the unit hydrograph (Chapter 5), which describes a catchment's unit response without regard to the response of individual subcatchments.

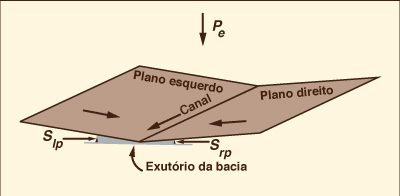

Unlike lumped models, distributed models have the capability to describe both temporal and spatial variations. Distributed models are much more computationally intensive than lumped models and are, therefore, ideally suited for use with a computer. A typical example of a distributed hydrologic model is an overland flow computation using routing techniques (Chapter 10) (Fig. 1-8). In this case, equations of mass and momentum (or surrogates thereof) are used to compute temporal variations of discharge and flow depth at several locations within a catchment.

Ao contrário dos modelos agrupados, os modelos distribuídos têm a capacidade de descrever variações temporais e espaciais. Os modelos distribuídos são muito mais computacionais do que os modelos agrupados e, portanto, são ideais para uso em um computador. Um exemplo típico de um modelo hidrológico distribuído é um cálculo de fluxo terrestre usando técnicas de roteamento (Capítulo 10) (Fig. 1-8). Nesse caso, as equações de massa e momento (ou substitutos) são usadas para calcular variações temporais da descarga e profundidade do fluxo em vários locais dentro de uma bacia hidrográfica.

Fig. 1-8 Two planes-one channel overland flow configuration. |

Solutions to hydrologic models can be either analytical or numerical. Analytical solutions are obtained by using classical tools of applied mathematics, such as Laplace transforms, perturbation theory, and the like [3]. Numerical solutions are obtained by discretizing differential equations into algebraic equations and solving them, usually with the aid of a computer. Examples of analytical solutions are the linear models used in hydrologic systems analysis [1]. Examples of numerical solutions abound, such as those used in hydrologic routing techniques (Chapters 8, 9 and 10) and in the computer models in current use (Chapter 13).

As soluções para modelos hidrológicos podem ser analíticas ou numéricas. As soluções analíticas são obtidas usando ferramentas clássicas da matemática aplicada, como transformadas de Laplace, teoria das perturbações e similares [3]. Soluções numéricas são obtidas discretizando as equações diferenciais em equações algébricas e resolvendo-as, geralmente com o auxílio de um computador. Exemplos de soluções analíticas são os modelos lineares usados na análise de sistemas hidrológicos [1]. São abundantes exemplos de soluções numéricas, como as utilizadas nas técnicas de roteamento hidrológico (capítulos 8, 9 e 10) e nos modelos de computador em uso atual (capítulo 13).

1.6 HIDROLOGIA DE INUNDAÇÃO E ESCALA DE BACIAS HIDROGRÁFICAS

|

|

At the catchment level, surface runoff typically occurs either: (a) when rainfall intensity exceeds the abstractive capability of the catchment surface, or (b) when the soil profile is completely saturated with moisture, with infiltration being reduced to negligible amounts. Eventually, large amounts of surface runoff originating at the catchment level concentrate to produce large flow rates referred to as floods. The study of floods, their occurrences, causes, transport, and effects, is the subject of flood hydrology.

At the catchment level, surface runoff typically occurs either: (a) when rainfall intensity exceeds the abstractive capability of the catchment surface, or (b) when the soil profile is completely saturated with moisture, with infiltration being reduced to negligible amounts. Eventually, large amounts of surface runoff originating at the catchment level concentrate to produce large flow rates referred to as floods. The study of floods, their occurrences, causes, transport, and effects, is the subject of flood hydrology.

In nature, rainfall varies in space and time. In engineering hydrology, rainfall can be assumed to be either: (1) constant in both space and time, (2) constant in space but varying in time, or (3) varying in both space and time. The catchment scale helps determine which one of these assumptions is justified on practical grounds. Generally, small catchments are those in which runoff can be modeled by assuming constant rainfall in both space and time. Midsize catchments are those in which runoff can modeled by assuming rainfall to be constant in space but to vary in time. Large catchments are those in which runoff can be modeled by assuming rainfall to vary in both space and time.

Na natureza, a precipitação varia no espaço e no tempo. Na hidrologia da engenharia, pode-se presumir que a precipitação seja: (1) constante no espaço e no tempo, (2) constante no espaço, mas variando no tempo ou (3) variando no espaço e no tempo. A escala de captação ajuda a determinar qual dessas premissas é justificada por razões práticas. Geralmente, pequenas bacias são aquelas em que o escoamento pode ser modelado assumindo chuvas constantes no espaço e no tempo. As bacias hidrográficas de médio porte são aquelas em que o escoamento superficial pode ser modelado assumindo que a precipitação seja constante no espaço, mas que varie no tempo. As grandes bacias hidrográficas são aquelas em que o escoamento superficial pode ser modelado assumindo que a precipitação varia no espaço e no tempo.

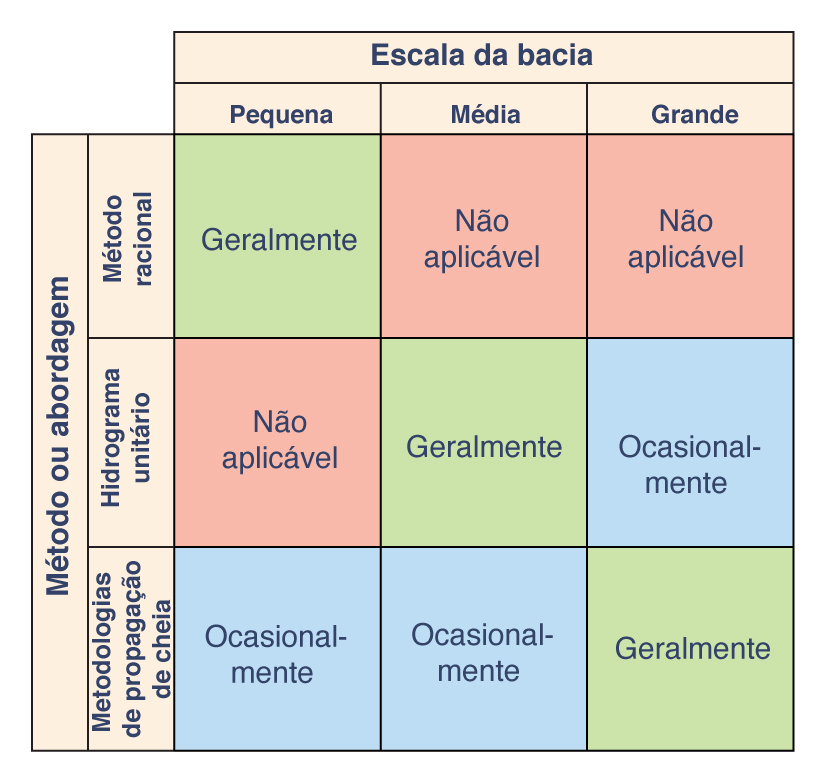

In flood hydrology, small catchments are usually modeled with a simple empirical approach, such as the rational method (Chapter 4). For midsize catchments, a lumped conceptual model such as the unit hydrograph is preferred by most engineers in practice (Chapter 5). For large catchments, temporal and spatial variations of rainfall and runoff may dictate the use of a distributed modeling approach, including reservoir and stream channel routing (Chapters 8 and 9). Figure 1-9 shows a matrix depicting the relationship between catchment scale and three commonly used approaches to flood hydrology.

In flood hydrology, small catchments are usually modeled with a simple empirical approach, such as the rational method (Chapter 4). For midsize catchments, a lumped conceptual model such as the unit hydrograph is preferred by most engineers in practice (Chapter 5). For large catchments, temporal and spatial variations of rainfall and runoff may dictate the use of a distributed modeling approach, including reservoir and stream channel routing (Chapters 8 and 9). Figure 1-9 shows a matrix depicting the relationship between catchment scale and three commonly used approaches to flood hydrology.

Fig. 1-9 Relationship between catchment scale and three commonly used |

The larger the catchment, the more likely it is to be gaged, i.e., to possess a streamflow record. Conversely, the smaller the catchment, the more unlikely it is to be gaged. This fact dictates that the probabilistic approach (Chapter 6) is primarily applicable to large catchments, particularly to those possessing a fairly long record period. For ungaged catchments or for gaged catchments with relatively short record periods, statistical techniques can be used to develop parametric models having regional applicability (Chapter 7). The subjects of catchment routing (Chapter 10) and catchment modeling (Chapter 13) span the gamut of hydrologic applications, from small to large catchments.

The larger the catchment, the more likely it is to be gaged, i.e., to possess a streamflow record. Conversely, the smaller the catchment, the more unlikely it is to be gaged. This fact dictates that the probabilistic approach (Chapter 6) is primarily applicable to large catchments, particularly to those possessing a fairly long record period. For ungaged catchments or for gaged catchments with relatively short record periods, statistical techniques can be used to develop parametric models having regional applicability (Chapter 7). The subjects of catchment routing (Chapter 10) and catchment modeling (Chapter 13) span the gamut of hydrologic applications, from small to large catchments.

QUESTÕES

|

|

- What is the hydrologic cycle?

O que é o ciclo hidrológico?

- Name the liquid-transport phases of the hydrologic cycle.

Nomeie as fases de transporte de líquido do ciclo hidrológico.

- Name the vapor-transport phases of the hydrologic cycle.

Nomeie as fases de transporte de vapor do ciclo hidrológico.

- What is a catchment?

O que é uma bacia hidrográfica?

- Give two examples of engineering problems (different from those mentioned in the text) where hydrologic knowledge is necessary to obtain a solution.

Dê dois exemplos de problemas de engenharia (diferentes dos mencionados no texto) em que o conhecimento hidrológico é necessário para obter uma solução.

- What is material model? A formal model?

O que é modelo de material? Um modelo formal?

- What is an iconic model? An analog model?

O que é um modelo icônico? Um modelo analógico?

- What is a deterministic model ? A lumped model?

O que é um modelo determinístico? Um modelo fixo?

- Contrast conceptual and parametric models.

Modelos conceituais e paramétricos de contraste.

- Contrast analytical and numerical solutions.

Soluções analíticas e numéricas de contraste.

- What is a small catchment from the flood hydrology standpoint? A midsize catchment? A large catchment?

O que é uma pequena bacia hidrográfica do ponto de vista da hidrologia de inundação? Uma bacia de médio porte? Uma grande bacia?

PROBLEMAS

|

|

During a given year, the following hydrologic data were collected for a 2500-km 2 basin: total precipitation, 620 mm; total combined loss due to evaporation and evapotranspiration, 320 mm; estimated groundwater outflow (including groundwater depletion), 100 mm ; and mean surface runoff, 150 mm. What is the change in volume of water remaining in storage in the basin during the elapsed year? (Volume in hm3, i.e., millions of cubic meters).

Durante um determinado ano, os seguintes dados hidrológicos foram coletados para uma bacia de 2500 km2: precipitação total, 620 mm; perda combinada total devido à evaporação e evapotranspiração, 320 mm; vazão estimada das águas subterrâneas (incluindo esgotamento das águas subterrâneas), 100 mm; e escoamento superficial médio, 150 mm. Qual é a mudança no volume de água restante em armazenamento na bacia durante o ano decorrido? (Volume em hm3, ou seja, milhões de metros cúbicos).

During 2012, the following hydrologic data were collected for a 85-mi2 watershed: total precipitation, 27 in.; total combined loss due to evaporation and evapotranspiration, 10 in.; estimated groundwater outflow (including groundwater depletion), 7 in.; and mean surface runoff, 9 in. What is the change in volume of water remaining in storage in the watershed during 2012? (Volume in ac-ft).

Durante 2012, os seguintes dados hidrológicos foram coletados para uma bacia hidrográfica de 85 mi2: precipitação total, 27 pol .; perda combinada total devido à evaporação e evapotranspiração, 10 pol .; vazão estimada das águas subterrâneas (incluindo esgotamento das águas subterrâneas), 7 pol .; e escoamento superficial médio, 9 pol. Qual é a mudança no volume de água restante em armazenamento na bacia hidrográfica durante 2012? (Volume em ac-ft).

During a given year, the following hydrologic data were collected for a certain 350-km2 catchment: total precipitation, 850 mm; combined evaporation and evapotranspiration, 420 mm; and surface runoff, 225 mm. Calculate the volume of infiltration (in hm3, i.e., millions of cubic meters), neglecting changes in surface water storage and groundwater effects.

Durante um determinado ano, os seguintes dados hidrológicos foram coletados para uma determinada bacia hidrográfica de 350 km2: precipitação total, 850 mm; evaporação e evapotranspiração combinadas, 420 mm; e escoamento superficial, 225 mm. Calcule o volume de infiltração (em hm3, isto é, milhões de metros cúbicos), negligenciando as alterações no armazenamento de águas superficiais e nos efeitos das águas subterrâneas.

During a given year, the following hydrologic data were measured for a certain 60-mi2 watershed: total precipitation, 35 in.; and estimated losses due to evaporation, evapotranspiration, and infiltration, 28 in. Calculate the mean annual runoff (in ft3/s). Neglect changes in surface water storage and groundwater effects.

Durante um determinado ano, os seguintes dados hidrológicos foram medidos para uma determinada bacia hidrográfica de 60 mi2: precipitação total, 35 pol .; e perdas estimadas devido à evaporação, evapotranspiração e infiltração, 28 pol. Calcule o escoamento médio anual (em ft3 / s). Negligenciar alterações no armazenamento de águas superficiais e nos efeitos das águas subterrâneas.

REFERÊNCIAS

|

|

Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. (1973). "Linear Theory of Hydrologic Systems," Technical Bulletin No. 1468. (J.C.I. Dooge, author). Washington, D .C., October.

Eagleson, P. S. (1970) . Dynamic Hydrology. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Lighthill, M. J., and G. B. Whitham. (1955). On kinematic waves. I. Flood movement in long rivers. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Vol. A229, May, 281-316.

Woolhiser, D. A., and D. L. Brakensiek. (1982). "Hydrologic Modeling of Small Watersheds," Chapter 1 in Hydrologic Modeling of Small Watersheds, edited by C. T. Haan et al. ASAE Monograph No. 5, St. Joseph, Michigan.

Yevjevich, V. (1972). Stochastic Processes in Hydrology. Fort Collins, Colo.: Water Resources Publications.

| http://ponce.sdsu.edu/hidrologia_engenharia/index.html |

|

200715 |